St. Isidore of Seville (560—636AD) holds a special role among the list given just now, as the patron saint of the right use of the internet for both Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christians, and so is the only one who the late philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre may have also named in his prayers. For the uninitiated, MacIntyre entered the mainstream of academia like a thunderbolt with ‘After Virtue’, now a cult-classic that serves as the manifesto for one of the three main vying ethical systems of Anglophone moral philosophy. In truth, MacIntyre consolidated a view that had been biting at the heels of analytic philosophy since G.E.M. Anscombe published her ‘Modern Moral Philosophy’. Between the two of them, Aristotelian-Thomism, and virtue ethics, have re-entered the canon of contemporary academia. This camp's opening proviso had been to call into question the stagnation of moral philosophy. Just as, centuries ago, Immanuel Kant had asked his peers what good all the millennia of debates on metaphysics had come to, a question that drove him to inventing the Enlightenment's most impressive systematic philosophy, so does the virtue ethicist camp begin;

“[Our] discussions generate an appearance of significant diversity of views where what is really significant is an overall similarity. The overall similarity is made clear if you consider that every one of the best known English academic moral philosophers has put out a philosophy according to which, e.g., it is not possible to hold that it cannot be right to kill the innocent as a means to any end whatsoever and that someone who thinks otherwise is an error. ... Now this is a significant thing: for it means that all these philosophies are quite incompatible with the Hebrew-Christian ethic. ... it would argue a certain provinciality of mind not to see this incompatibility as the most important fact about these philosophers, and the differences between them as somewhat trifling by comparison. ... [And yet] it is noticeable that none of these philosophers displays any consciousness that there is such an ethic, which he is contradicting.„ — ‘Modern Moral Philosophy’ (1958) by G.E.M. Anscombe (1919—2001)

It would be inaccurate to say that every English moral philosopher ‘since Sidgwick’ were wittingly flouting Christian ethics. Indeed, many—perhaps most of them—were practicing Christians, at least nominally. And certainly more in Anscombe's day than MacIntyre's—and still more then than now—academia, and society broadly, retained many leftovers from its Christian cultural heritage. Yet the thrust of this camp was to show that, historically speaking, we had long philosophically subverted that heritage at large, Christians and non-Christians alike. For a Christian, this is not groundbreaking news today. For a non-Christian, this is not especially troubling in itself. What MacIntyre did was to give force to the point, to demonstrate it with a genealogy from Aristotle to the present day, and to raise the stakes dramatically. If Anscombe is right, then it follows that our moral philosophy has been deprived of what it imagined was a foundation. Then we need to, as Kant sought to do for metaphysics, return to investigating our moral foundations. I will not recount the whole book here, since it is both well-established and an enjoyable read for its scope, but MacIntyre inquires into each competing strain in early-to-late modern philosophy. His conclusion (and introduction!) is taken from the pages of Walter Miller's ‘A Canticle for Leibowitz’, a post-apocalyptic novel written in 1959. In this novel, what we know as global, modern society has long collapsed. Indeed, it is so long ago that nearly all memory of it is lost; monks in the desert, on occasion, reclaim miraculously preserved grocery receipts, which they interpret as holy writings from early saints. MacIntyre's point is to show that all our moral language today are such holy relics; we do not have the context, or historical awareness, of what they were once used for, but we go on pretending like we do, unaware of our situation. And it is this fact that lends us to today's predicament of everyday disputes between people being a matter of ‘your truth’ and ‘my truth’, ethical arguments in which no possible victor can triumph since it all boils down to presuppositions and ambiguous feelings of like or harm, and, consequently, a political culture which is defined by a return to an old argument given by Thrasymachus in Plato's ‘Republic’;

“... each makes laws to its own advantage. Democracy makes democratic laws, tyranny makes tyrannical laws, and so on with the others. And they declare what they have made—what is to their own advantage—to be just for their subjects, and they punish anyone who goes against this as lawless and unjust. This, then, is what I say justice is, the same in all cities, the advantage of the established rule. Since the established rule is surely stronger, anyone who reasons correctly will conclude that the just is the same everywhere, namely, the advantage of the stronger.„ — ‘Republic’ by Plato, translation by G.M.A. Grube and C.D.C. Reeve (1997)

Political realism, as we may call this, is only one of many answers to the crisis of groundlessness. There are others, such as emotivism (all of our moral and ethical language is really an expression of fundamental emotions in us; so ‘that is wrong’ really has no more meaning than ‘that makes me unhappy’), intuitionism (morally speaking, that we all have basic underlying moral ideas that tell us what is right or wrong), and cousins from without analytic philosophy such as evolutionary psychology (all of our moral values are set by patterns that derive from biological habits acquired via evolution hundreds of thousands of years ago) and social constructivisms (which, even being fair, are really just affirmations of Thrasymachus's political realism). What all of these share in common is that they lack any stable criteria for value concepts like the good and the just (which is relevant for Plato, since he inherited a similar situation). Consequently, we use these values flippantly, and since even the best of us manipulate these when we need to, these values mean nothing. In our society there is no good and just, and so Thrasymachus's description is, ironically, proven true; by being spoken it makes itself true. If there is no good and just, then all the good and just we think there is are fictions, and if they are fictions, then material conditions (such as political power, cultural influence, or class relations) will dictate what fictitious ‘justices’ are socially permitted. Across liberal democratic political spectra this is the prevailing attitude. ‘If we win, then our ideas of justice will prevail, and this will be better for these material reasons.’ But more urgently, ‘if we do not win, then our ideas of justice will perish.’

MacIntyre's conclusion also invokes St. Benedict, who becomes the emblem of Rod Dreher's ‘The Benedict Option’. Yet besides this, have Christians—as MacIntyre predicted—retreated from society at large? On the contrary, those Christians who express feeling the most threatened by modern culture insist on seizing it by the reins. There is something evocative of political realism in Christian civil participation today; as if failure means the demolition of Christianity, even as in the Book it was written, ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it’ (Matt. 16:18). Yet it seems plausible that they do more damage than good to their situation. For if the political realities are one shaped by conditions of realism, then for any well-meaning person to prevail, they will have to be a realist. From my time in political life, I can attest to how many politicians the public holds to be ‘weaselly’ or ‘distrustful’ by nature really did begin with gentle souls and good-intentioned hearts. How much is left after their trials and tribulations? Doesn't the same question apply to each and every political Christian? And again, was it not written, ‘if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell’ (Matt. 5:29)? Will one Christian with a possibly good heart succeed where every other person has failed? They might have faith that they will succeed; would this be a faith in themself, or a faith in God? If it were to be shown to be the latter, then they would have to be willing to say, with all seriousness, ‘the Lord needs me to go into politics, and to succeed.’ This is why I suspect all attempts of this kind, in liberal democracies, will fail. Our politics is shaped by a basic condition of egoism, false self-glorifying, deceiving others, and, worst of all, deceiving oneself. One could not survive the long, arduous siege-like elections and sessions if one did not deceive oneself from time to time. But then one acquires the habit of ‘losing oneself’ in the lies. And from there, we can consult Søren Kierkegaard;

“The greatest hazard of all, losing the self, can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all. No other loss can occur so quietly; any other loss – an arm, a leg, five dollars, a wife, etc. – is sure to be noticed.„ — ‘The Sickness Unto Death’ by Søren Kierkegaard, translated by Howard & Edna Hong (1983)

For reasons similar to these the leading philosophers of today's culture, such as Charles Taylor, fixate on themes of authenticity or self-constitution. Implicit here is a recognition that we are today wont to lose ourselves, or fail if ever to ‘find’ ourselves. The pressures that force well-meaning politicians to conform is, really, just the social pressure to conform; whenever one enters into a public space and speaks, one feels that pressure. Christians today might wish to pride themselves on their being anti-conformist, but so long as they insist on social media, political participation, and regional, national, or international business interests, they cannot be but influenced by whatever it is they're decrying. Likewise, progressives and atheists hold themselves to be anti-conformist, standing opposed to the tradition of Christianity and fundamentalist conservatism. We are all anti-conformist. None of us are. Whatever it is we actually do, however it is we actually act, makes up what is really the standard today. One look in that direction is far bleaker; too many of us are global consumers, enjoying products which the six-continent exchange has facelessly passed onto us at privileged rates. Now is a good chance to talk about the opposite of our active complicity and engagement with these things; what if we self-isolated, as Dreher wishes—what if we retreated from these corrupting spheres of modern life? Whatever our religion, or whatever our culture, or whatever, even, our individual self may be, can we avoid the pressures by isolating from them?

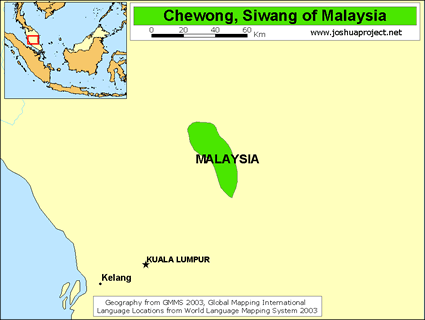

Cultural anthropology has long been interested in isolated indigenous peoples. The Cheq Wong serve as one valuable example in the studies of Signe Howell. They are of interest because of their cosmology; cultures exist whose worldview, language, and metaphysical assumptions are so vastly different from our own that studying them may lend us a clearer idea of what ‘humanity’ really means. But the Cheq Wong are only one case-study; there exist countless, not only among anthropologists, but among authors too, such as Wole Soyinka, whose works are relevant in the impacts of modernity on Yoruba culture. For as soon as we have taken an interest in the Cheq Wong, we have broken that isolation, and cross-contamination is already happening. Or so it would—if we had a grounded culture to transmit, with coherent frameworks. Does, then, Cheq Wong or Yoruba culture win out over us? Some conservatives have tried to see the state of affairs in this way, but it fails to account for the facts of the indigenous; their cultures are being changed, indeed often annihilated, by something, even if not by us. This is partly the relevance, for example, of postcolonial studies, despite all its false premises; it sets our attention in the right direction. The real problem is that of economy; it seems naïve today to think that the only local communities the global exchange of the future will leave untouched are those that lack the competence or capacity to keep the world at bay. Moreover, modern society creates pressures that, if these isolated groups fail to meet them on modern terms, will destroy them. As soon as a community has entered the fast-increasingly technologically advancing interdependent world we've built, they are incentivized to undergo the major economic developmental steps that culminate in their partaking in a world culture. At the very minimum they will engage with the internet. If they choose not to take these steps, whatever their cultural costs, they remain at the bottom rung of the global exchange, and are liable to be forced into de-facto slavery for the baseline production of goods, or made to suffer unconscionable acts at large scales as unprotected peoples.

Suppose they do take these steps; they attain the baseline economic access to the internet and no more. We cannot fault him for it, since no philosopher can predict with perfect accuracy the future, but the internet has ‘changed the game’ as it were. It is that MacIntyre (and Dreher's) communitarianism was too embodied, too physical; it treated the entity they were evaluating like something physical, even if only via physical relations between people and objects. But the internet disseminates culture far quicker and far more efficiently than previously thought possible. Where there is information there is language; where there is language there is culture. Futurists do not think any longer in purely material, physical terms. The internet has become a hyper-real space defined by disembodiment and the lack of borders. If, here, we cite the crises across countries with high internet use (or high development) and declining birthrates, rapidly declining social connection, we can see the effects of digital disembodiment. Children raised on the internet have elements and building blocks in their upbringing that cannot be found or traced in the real world. They ultimately fantasize about different cultures, worlds, or even selves; they become dissatisfied with living in this country, in this world, or in this body that is theirs. Economic pressures seem to incentivize parents to leave their children to their devices, which obliterates whatever was left of the ordinary developmental cycle we humans have had for many millennia. Toddlers access media that is built to catch their attention and keep it. Adolescents, teenagers, and young adults do the same.

All of this occurs with a shared feature, the predatory business model that makes the viewer and user, the infant, child, or young adult, the product when they think they are the customer. Thus they are moulded into being more product-like, while the media is moulded to be more desirable and more profitable. During all of this must occur an obliteration of inherited culture. No longer is it even under the guise of ‘enlightenment’, ‘rationality’, ‘success’, or even ‘anti-conformity’ that we see people lose themselves. Now it is simply their passions that do it, passions instilled in them and fueled from infancy onwards. We have produced people who cannot resist their inclinations, who cannot even recognize those inclinations, by a massive neglect, and those people in turn will begin producing people, and producing media, all perhaps to fuel their continued and worsening habits. As a byproduct, everyone and everything in nature has been objectified for gratification, and people are growing incapable of failing to objectify anything at all. How can a people which has suffered multiple generations of this find anything sacred?—on this score, the fundamentalists seem to be intuitively right: it really does appear that our options are dwindled to only one, that is, try to change things now, or to invite worsening conditions until the gates inevitably burst open. But we saw that this route too seemed probably closed. What is the way out? If there is no way out, what are we to do? Moreover of the digital age our old concepts do not meet the scale and newness of the invention. It has happened so quickly, so overnight, as to go undetected as the great threat—or it is simply unavoidable that we should accept it; after all, we are all here now. But, for the most part, what I have just said is wrong; there is a precedent, and it is the written word.

St. Isidore wrote prolifically. His study covered such a wide breadth as to make him significant for much of the Middle Ages for his ‘Etymologies’, a compendium of all the known facts available to him, from grammar and rhetoric to biographical histories and philosophy to even agriculture and smithing. It is this vast learning that makes him an ideal patron saint for a place whose promise (and curse) is exponentially increasing information at our fingertips. Studying herbology, astronomy, pagan philosophers, and heretical arguments on Christology had not dampened his convictions in the least. By contrast, we can turn to Islamic attitudes toward such threats; the Wahhabi condemnation of all ‘falsafi’, the veiling wholesale of women, the quartering of them in different homes, etc. Where there is a risk it is isolated, shuttered, or exterminated. But St. Isidore covered all the forms of knowledge that later Christians would find sufficiently threatening to (at least publicly) reject and refuse at face-value. Perhaps here is a grain of relevant truth. The Etymologies will be written whether by an Orthodox Christian or an Arian; it is simply a question of who will write it, and who will one day read it. At the same time, of our many travails, Blessed Fr. Seraphim Rose of Platina once received a question while on a walk from a man on how to overcome homosexuality. Fr. Seraphim's answer was to point to a rattlesnake rearing aggresively on the road and say to him, "As we must run from this snake, so too run from homosexuality!"—so we should, it seems, treat those things that cause us to fall. Thus we have formed here two clear competing alternatives; retreat or presence. Of the former we may focus on not losing ourselves but lose others. Of the latter we may bring others to our cause, but lose ourselves, and then one must wonder whether we have helped anybody after all. St. Isidore nevertheless retains that ancient and lost sentiment; that we have these things called computers, that tap into such a thing as the internet, and that, of all the many uses we can imagine working with it as an instrument, there is one proper use for it, its inherent purpose. So with the body; so with sexuality; so with all things under the sun.

Part of what we have lost is the capacity to recognize true purposes in things; if something can be misused, we incline toward isolating, shuttering, or exterminating that thing. But if this is true of all things, then it follows that a walk in the garden should not be peaceful and pleasant, but harrowing and silent. All things seem to us capable of evil. Of course, the bees may soon rise against and brutally kill their queen; the tree roots will starve and strangle the flowerbed; the flies will carry germs from rot to the pond and the fishes are always slaughtering one another. But we tell ourselves that there is no evil in it; it is simply their nature. We, however, cannot answer an indiscriminate murder with ‘it was their nature’—we must make choices; we must hold others accountable for their choices. All choices are of what to do, and how to use, the gifts one has at their disposal. To use this flower to bring delight to your children, or to use it to poison the noisy dog next door. To use this ability to grow animals for resources well, or to factory farm these animals in unconscionable, indefensible conditions. To use this fascinating mechanic invention to hunt, or to use it to indiscriminately kill from afar. For this reason, Christian peoples in history had not found it necessary, or even good, to veil women from head-to-toe. The women's bodies were not evil, not even shameful; the source of the sin is that eye, and our Lord told us to pluck our eyes out before we cast the blame on her. When He spoke of lust, as when do the Desert Fathers, it is a condition in us, and not one we can project onto the other. Finally, in the Garden, Adam blamed Eve; why should it have been so written if it was truly and entirely her fault? From these considerations we should be prohibited from blaming the internet as an object or technology, just as we should be prohibited from blaming anything for our mistakes. But it remains true that they pose great dangers to us, these dangers are almost unavoidable; yet we should have been able to suffer and endure them, as St. Isidore had. For throwing everything away because it is all frightening is also a mistake, if it prevents us from using the gifts we have been given well, as they are intended to be used. We are called to remove our own sin on us, not to remove the thing our sins used; it seems to me that we are called to accept responsibility.

I am writing here because I am straddled between these concerns myself. In my studies, I have been able to disintegrate the certainty I had in the pessimistic futurism that this world seems headed toward; however, it has left me with more questions and fewer answers. On the other hand I have also come to grips with the fact that where I loathe the internet, I ought to have challenged myself; where anyone these days grows up on the internet, they are deprived of often even the chance to recognize that there is a true end and good purpose for the internet. If I have any semblance of an idea of what this purpose would look like, but I throw it away out of fear and blame, then I would find it hard to answer for that mistake. So in this overwrought manifesto of my own, I have illustrated many of the pressing concerns that yield one to a view of the internet which I have come to adopt; reticent, wary, but perhaps no longer entirely dismissive. In my own way, then, I will collect here the things I think might be a good use of this tool, and in so doing continue to run from those things and places that continue to invite me to lose myself. I do not expect I will achieve much here, but in this isolated corner of the internet, I can at least write about and include the little things I've found.